The Tasmanian devil, the scrappy marsupial of Looney Tunes legend, should be long gone.

Since 1996, a contagious cancer has killed 80 percent of devils’ overall population — and up to 95 percent in certain locations. Based on how the disease spreads, experts predicted in 2012 that the Tasmanian devils would eventually fall into extinction.

But a new study, published Tuesday in Biology Letters, offers fresh hope by showing a small group — six devils — have mounted an immune response to the disease in northwestern Tasmania. Though the furry critters aren’t clear of danger, the results may represent a turning point for the island’s most important predator.

“We were excited!” said Ruth Pye, a veterinarian and PhD candidate at the University of Tasmania who co-authored the study. “It was really encouraging to find evidence that the tumors could be ‘seen’ by the devil’s immune system.”

Disease models favored extinction, yet researchers weren’t seeing eradication in some of the longest diseased populations.That’s because the condition — devil facial tumor disease — had been thoroughly monitored across Tasmania for years without a hint of natural immune response. The tumors spread from face to face via bites — without hesitation. These bites usually happen during mating season, so the cancer spreads like an aggressive sexually transmitted disease.

Part of the disease’s potency results from its weird origins. The mammalian immune system has evolved sophisticated tools to reject foreign invaders, such as viruses and bacteria, but this pattern extends to tissue from other animals. (Hence, why organ transplants in humans are so often rejected by recipients.) As a result, infectious cancers are rare, with the only other known examples in nature occurring in domestic dogs and soft-shell clams.

Tasmanian devils are important predators that keep invasive species like feral cats and foxes in check. Photo by Mariusz Prusaczyk/via Adobe

Twenty years ago, a single tumor in a single female Tasmanian devil mutated to bypass this evolutionary shield. The mutation tamps down a recipient’s MHC I pathway, which is the immune system’s version of a car alarm. Without it, the tumors can essentially hide from the immune system upon landing on a new face. The disease becomes fatal as the tumors swell inside the devils’ mouth and throat. Infected animals tend to die within six months to a year.

“As the tumors progress, they can interfere with the devils’ ability to eat, leading to starvation,” Pye said. Death can also happen when the tumors spread to other body parts and cause subsequent organ failure.

Disease models favored extinction, yet researchers weren’t seeing eradication in some of the longest diseased populations. The turning point came in 2011 when Pye’s colleague, ecologist Rodrigo Hamede, noticed a few cases in northwest Tasmania where the tumors had regressed. Hamede had been studying devils in the region since 2006, when the outbreak first arrived in that part of the island. Their team examined blood samples from 52 devils, covering a period from 2008 to 2014.

They discovered six animals had produced antibodies to attack their tumors. Antibodies are the immune system’s way of tagging a foreign invader for disposal, and these ones indicated that the devils’ MHC I pathway was working. Tumors regressed in four of the animals.

One remained disease-free for three years up until the age of six, which tends to be the maximum lifespan for a Tasmanian devil in the wild. Two devils caught the disease around the age of five but witnessed tumor regression in the same year. One devil saw the cancer return after two years of being disease-free, while the final pair in the bunch didn’t display any regression.

It’s the first overt evidence that the devils bodies are mounting a resistance. But other hints preceded it.

In August, geneticists led by Andrew Storfer of Washington State University reported signs that the devils’ genomes were rapidly changing to cope with the disease. They looked at three populations of the devils, examining samples from before and after the disease had infiltrated the area.

“We found strong changes in seven genes, five of which associated with cancer risk and immune function,” Storfer said.

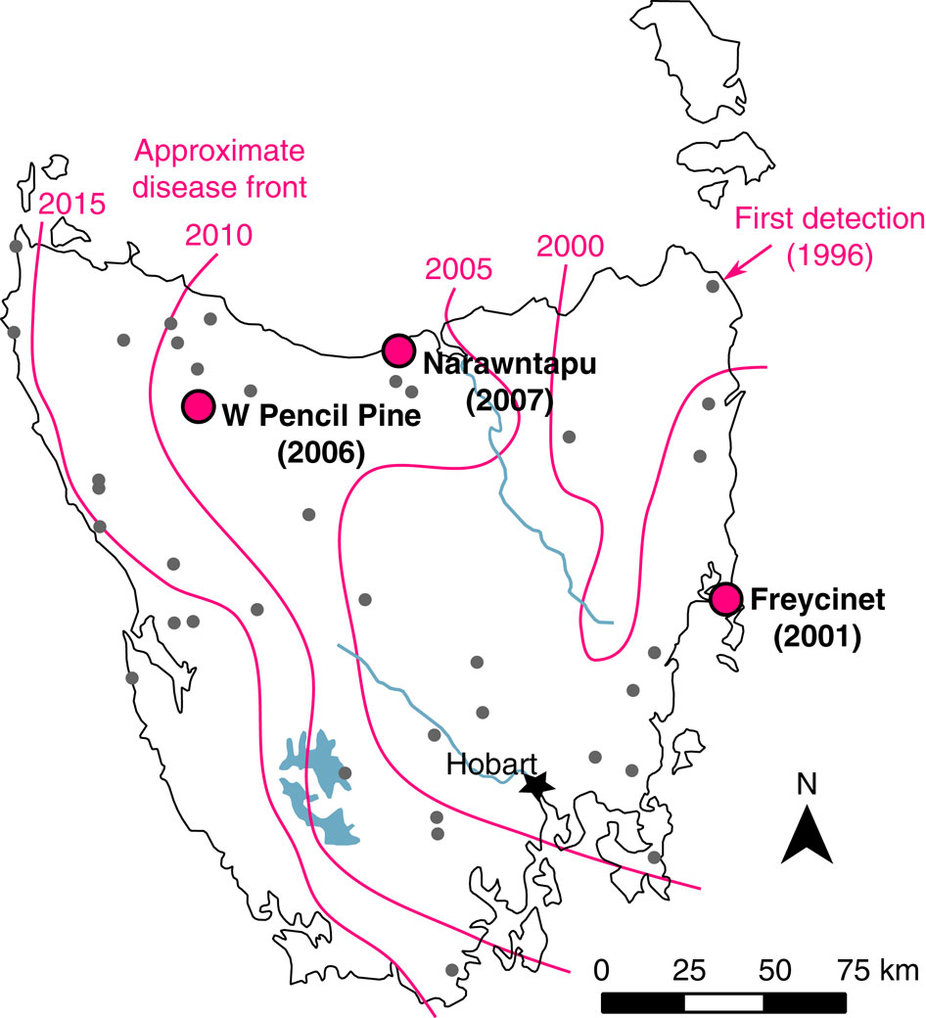

Devil facial tumor disease first appeared in Tasmania’s northeast corner in 1996. The magenta lines indicate the approximate location of the disease front in 2000, 2005, 2010 and 2015. The dots show populations analyzed by Andrew Storfer and his colleagues. Illustration by Epstein B et al., Nature Communications, 2016

He explained that such a strong evolutionary response was “pretty unusual” because it occurred in just 46 generations of Tasmanian devils. Adaptations to a genome — the hardwired playbook for any organism — typically take longer.

But other indicators had emerged too. Last week, a study reported Tasmanian devil milk can kill superbugs — antibiotic resistant microbes — and potentially combat the facial tumors. This may partially explain why young Tasmanian devils don’t catch the facial tumors. And last winter, a 10-year investigation found the tumors themselves appeared to be adapting to allow the devils to live longer.

The signs point to the devils’ adapting to survive long enough to reproduce. For instance, even though a second version of the tumor disease emerged last year, but Pye’s team has already found preliminary evidence that the devils can mount an immune response against it too. Overall, their findings may lay the foundation for a vaccine against the tumors.

Extinctions caused by infectious diseases are rare, and a series of studies show both Tasmanian devils and their facial tumors are evolving to keep the marsupial alive. Photo by Mariusz Prusaczyk/via Adobe

But the animals aren’t free and clear yet.

“If you have a die-off of 90 percent in most populations, it creates a problem,” Storfer said. “Low genetic variability and inbreeding can cause other defects, and perhaps a lack of abilities to respond to other environmental changes.”

The rebound may complicate conservation efforts too. In 2012, scientists transferred a batch of disease-free Tasmanian devils to nearby Maria Island to establish a breeding colony. If the Tasmanian population is evolving, and they reintroduce individuals from the breeding colony, then they could effectively start diluting the natural immunity that has started to emerge.

“We need to think very carefully about these results moving forward,” Storfer said. “But together, our studies give hope.”

ncG1vNJzZmivp6x7sa7SZ6arn1%2Bjsri%2Fx6isq2ejmLamusKeZq2Zo6Kur7XAp2SdnaaeubR5wpqlnJ2iYrK5wMinmq2hn6M%3D